The Bodybuilder as (Martial) Artist

“Creating—that is the great salvation from suffering, and life's alleviation. But for the creator to appear, suffering itself is needed, and much transformation.” – Nietzsche

Plato was wrong about the beginning point of culture. He purported, like many a philosopher after him, along with the entire Christian religion, that it was the soul, ψυχή (distinct from Pneuma (πνεῦμα)), that lay at the center of man. This has been the natural Western attitude since Plato, but it is flawed. Nietzsche argued something much more actionable and beautiful: for him, the body was at the center of everything because it alone could apply force in the world. Physicality, health, vitality—these are remnants of a culture long discarded. But at what cost? The cost of life itself.

Indeed, Nietzsche, in his study of the societies, religions, and cultures of the ancients through to the late 19th century, uniquely observed that the Greeks “remain the first cultural event in history" and that in preferring equal seriousness in the training of both body and mind, “they knew, they did, what was needed”. They not only “knew” but also “did”, and they did so gloriously. Modern philosophers, those priestly, soft-bodied, half-men populating universities and World Economic Forums alike, have not even ever considered “the body, the gesture, the diet, physiology” as real things, or as philosophical objects, from which Nietzsche believes “the rest [of culture] follows”. They discarded the idea of the body as a significant aspect of being, life itself. And they did so out of weakness.

Nietzsche saw art and drama as cornerstones to the greatness of Ancient Greek culture. Indeed, they are culture at its most representable. Could one then imagine a better example of high culture, of the kind of ‘aristocratic radicalism’ which Nietzsche identified with, than bodybuilding? Classical bodybuilding, being the most fitting way to describe it, is the very definition of culture from a Nietzschean viewpoint. It is one of the most essential and defining activities of a healthy, beautiful culture. Who should believe it coincidence that the Greeks, whom invented and popularized science, drama, cultural activity itself as we think about it now, that they also invented the Olympics?

Physical culture is the only real culture, and the bodybuilder is its premier artist. He is both master and emissary of art and reality, the marble and the sculptor. He is an aesthetic phenomenon, that is, a piece of art, but also something much more. As Nietzsche wrote in The Birth of Tragedy,

“We have our highest dignity in our significance as works of art – for it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.”

If this is true, how could we expect to feel fulfilled today? In a world where forty-percent of the population is obese or significantly overweight, and almost no one trains physically at all, how could we feel our suffering justified? How could we truly come to know ourselves at all in the absence of bodily awareness? Of course, suffering is inescapable. Its nature is tragic; it is either confronted today or made worse tomorrow. Art, artistry, creation, the aesthetic sense; in these phenomena we find redemption—they are the natural fruits of a strong will’s confrontation with suffering. Through art and the realization of taste, we come to be at peace with the beautiful chaos of nature.

Bodybuilding, being a form of artistic creation, becomes a worldly justification in the mind and body of the conscious bodybuilder. It is also a natural means to the cultivation of long-term health and physical energy. Most of modern bodybuilding fails in this way. It is neither healthy nor beautiful. It does not promote life in the individual but instead is sacrificed to life, as an antagonist to life. Silver Era legends like Steve Reeves and Reg Park embodied the ideal of natural bodybuilding and healthy physical culture. Golden Era figures like Schwarzenegger, Frank Zane, Franco Columbu, and Mike Mentzer maintained a largely healthy lifestyle whilst pushing aesthetic standards even higher. These are Übermensch, Super Men, anti-Last men. Not their personal character in all its aspects per say, but as aesthetic phenomena, as works of art. Nietzsche's comments on the psychology of the artist map on perfectly to the consciously realized classical bodybuilder,

“In [the artistic] state one enriches everything out of one's own fullness: whatever one sees, whatever one wills, is seen swelled, taut, strong, overloaded with strength. A man in this state transforms things until they mirror his power––until they are reflections of his perfection. This having to transform into perfection is––art. Even everything that he is not yet, becomes for him an occasion of joy in himself; in art man enjoys himself as perfection.”

The bodybuilder and the artist are one. A culture’s very bones are built from their work: it is hollow without them, just as a physique is rendered hollow absent a strong pair of legs and glutes. Furthermore, “art is essentially the affirmation, the blessing, and the deification of existence.” It is “the proper task of life”, according to Nietzsche. Epictetus also described living itself as a form of art, for, as discussed, it can only be justified as such. Bodybuilding then, having been established as an artistic pursuit, is justified on aesthetic grounds—and on aesthetic grounds alone. This does not negate however its plethora of practical applications, especially as a tool for use under a martial purpose.

The notion that natural (classical) bodybuilders are “muscle-bound” or in some other way less capable of moving and physically performing than less muscular individuals is simply absurd. Strength is always an asset. Even more so in the realm of combat and martial arts. A well developed physique performs moves more explosively, more elegantly, more powerfully. It is the practical justification of itself, beyond the mere aesthetic (although the two are intimately related; after all, why would muscle growth occur as a result of external resistance stimulus if it was not to serve the purpose of survival?). The classical bodybuilder is the universal athlete and represents the highest aesthetic state of man—man as a work of art.

Posing, the flexing of the muscle, the fluid movement between poses. How could it be anything but art… yes, life! It is in posing, in the presentation of musculature on the bodybuilding stage that he, the bodybuilder, reaches his peak as art. He is nobly represented and filled with strength when he presents his routine. His will to power is shining strong. Modern man knows nothing of this energy.

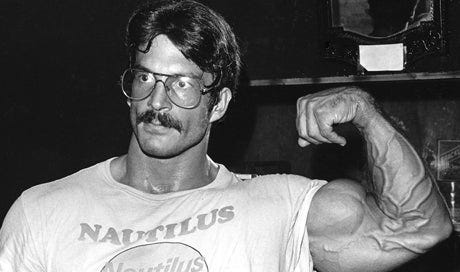

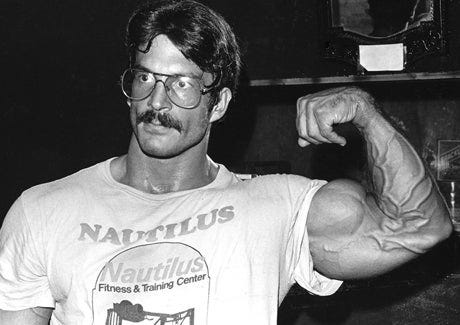

Bodybuilding already has a history of being paired with philosophical pursuit and consideration. Eugene Sandow, often referred to as the father of modern bodybuilding, wrote about bodybuilding and its significance for man. His 1919 work is entitled Life Is Movement: The Physical Reconstruction and Regeneration of the People. He was a man aware of the importance of exercise, and perhaps especially bodybuilding, as a central means toward spiritual and cultural health, and redemption. Mike Mentzer (mentioned earlier) was a philosopher himself and wrote several books on his bodybuilding methodology, being the original source of a theory of HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training) style training for muscle hypertrophy. He at once stated, “Man is an indivisible entity, an integrated unit of body and mind” and that indeed “his proper stature is not one of mediocrity, failure, frustration, or defeat, but one of achievement, strength, and nobility.” He described Nietzsche as “the only philosopher who ever really stimulated [him].”

Of course, the gymnasium of the Greeks was a place constructed and run with this exact sentiment in mind. Men would gather to train their bodies and engage in intellectual pursuit simultaneously. This included lifting weights to build muscle and strengthen the body, as well as wrestling and other types of combat and competition. Plato himself was known as a prolific and skilled wrestler before he became the great philosopher. He endorsed the idea of the scholar-athlete:

“He who is only an athlete is too crude, too vulgar, too much a savage. He who is a scholar only is too soft, too effeminate. The ideal citizen is the scholar athlete, the man of thought and the man of action.”

It would be Nietzsche, however, who would come to see Plato’s physical achievements as among his most worthy efforts; perhaps, he might have said, even more so than his philosophy.

Furthermore, men competing and training at the gymnasium did so in the nude (gymnós meaning "naked" or "nude"). This was done with an aesthetic purpose, a display to honor the gods. The Greeks, very unlike our culture today, admired and esteemed the beauty of the male body. Today, in our perverse and ugly culture, the beer (soy) belly, oversized football jersey promoting another man’s physical achievements, and 11-inch basketball shorts reign supreme as masculine aesthetic standards. Western man’s body has been broken down and shamed into obscurity and softness by hysteria around homosexuality and a hormone decimating diet. Only a weak, fragile masculinity would allow the existence of gay men to preclude its ability to express itself freely and with pride. The weekly football-watching, beer-drinking “man’s man” (as much a Nietzschean ‘last man’ as any video game obsessed, reddit moderating, pronoun declaring dweeb), uses accusations of homosexuality as cope for his insufficiency in the eyes of mother nature.

Masculinity does not exist in its most realized form without the beautification of the body, for the source of its beauty is strength, achievement, and readiness (unlike that of the female body, which comes from purity, gentleness, and the prospect of ultimate fulfillment in pregnancy). The greatest cultures in human history understood this very well, and without exposition. Its conscious instantiation today (and eventual unconscious integration), that of health, natural beauty, artistry in lifestyle, organization of the passions—this is the key. Life, nature must prevail.